El Niño is the name given to the occasional development of warm ocean surface waters along the coast of Ecuador and Peru. When this warming occurs the usual upwelling of cold, nutrient rich deep ocean water is significantly reduced. El Niño normally occurs around Christmas and usually lasts for a few weeks to a few months. Sometimes an extremely warm event can develop that lasts for much longer time periods. In the 1990s, strong El Niños developed in 1991 and lasted until 1995, and from fall 1997 to spring 1998.

The formation of an El Niño is linked with the cycling of a Pacific Ocean circulation pattern known as the southern oscillation. In a normal year, a surface low pressure develops in the region of northern Australia and Indonesia and a high pressure system over the coast of Peru (see Figure 7z-1 below). As a result, the trade winds over the Pacific Ocean move strongly from east to west. The easterly flow of the trade winds carries warm surface waters westward, bringing convective storms to Indonesia and coastal Australia. Along the coast of Peru, cold bottom water wells up to the surface to replace the warm water that is pulled to the west.

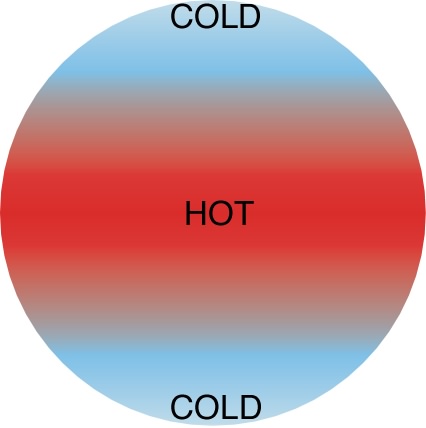

Figure 7z-1: This cross-section of the Pacific Ocean, along the equator, illustrates the pattern of atmospheric circulation typically found at the equatorial Pacific. Note the position of the thermocline.

In an El Niño year, air pressure drops over large areas of the central Pacific and along the coast of South America (see Figure 7z-2 below). The normal low pressure system is replaced by a weak high in the western Pacific (the southern oscillation). This change in pressure pattern causes the trade winds to be reduced. This reduction allows the equatorial counter current (which flows west to east) to accumulate warm ocean water along the coastlines of Peru and Ecuador (Figure 7z-3). This accumulation of warm water causes the thermocline to drop in the eastern part of Pacific Ocean which cuts off the upwelling of cold deep ocean water along the coast of Peru. Climatically, the development of an El Niño brings drought to the western Pacific, rains to the equatorial coast of South America, and convective storms and hurricanes to the central Pacific.

Figure 7z-2: This cross-section of the Pacific Ocean, along the equator, illustrates the pattern of atmospheric circulation that causes the formation of the El Niño. Note how position of the thermocline has changed from Figure 7z-1.

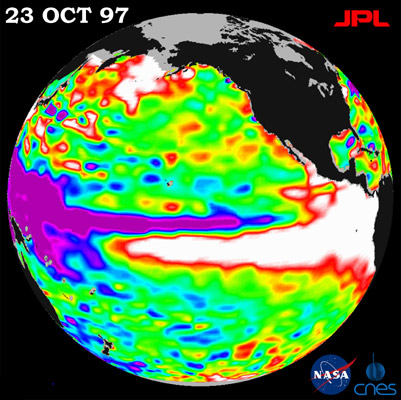

Figure 7z-3: NASA's TOPEX/Poseidon satellite is being used to monitor the presence of El Niño. Sensors on the satellite measure the height of the Pacific Ocean. The scale below describes the relationship between image color and the relative surface height of the ocean. In the image above, we can see the presence of a strong El Niño event in the eastern Pacific (October, 1997). The presence of the El Niño causes the height of the ocean along the equator to increase from the middle of the image to the coastline of Central and South America. (Source: NASA - TOPEX/Poseidon).